How much is your vote worth?

In Libya or Syria the right to vote may be worth a life. However there’s little in the way of basic freedoms and a low standard of living. There is everything to play for in comparison to a Western democracy where you have many established rights and the standard of living is higher still.

In Western democracies like the UK or USA voting actually seems irrelevant for many people: for example 35% (UK) and 43% (USA) of voters didn’t vote in their respective elections in 2010 and 2008.

Are these Western non-voters irrational or irresponsible? Is it just that they don’t understand their duty to the community and we need to improve the teaching of Civics in schools?

In Australia this question has special resonance – because of these three English-speaking countries only Australia actually makes it compulsory to vote. You get fined if you don’t.

What’s even more interesting is that Australians, who have been accused of having a chip on their shoulder about their culture versus older cultures, often seem to regard compulsory voting as evidence of the innate superiority of their political system to that of the US or UK.

But let’s come back the ‘value’ of your vote. What’s it worth? And are there really cases where it’s worth nothing despite what it may be worth in Libya or Syria?

Is your vote worth nothing?

Voting seems of negligible value if:

- you are a resident of a safe seat (your vote aint going to make any difference to political outcomes anyway)

- all parties seem to have relatively similar policies on the issues that matter to you

- you believe that parties have relatively little influence on the machinery of government (the average ministerial term is under 2 years last time I checked – the Humphrey Applebys of this world are the the people that matter and not the politicians)

- you strongly disagree with at least some of the policies for say the 2 major parties that have a chance of winning government

- you believe that there is a tenuous causal relationship at best between a vote once every 4 years for your local member and the policy outcomes of a multi-member government

- you had something personally more important to do on the day of the election

- you wish to vote in an informed way but were unable for various reasons (lack of time, lack of information) to ascertain whether the party platform made sense

- you believe that other members of your community will keep the politicians in check and your involvement is therefore not necessary at the time

Is your vote worth less than nothing?

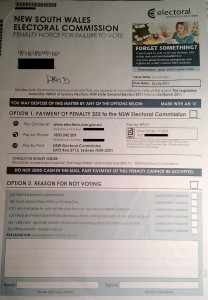

Possibly the best evidence that voting can have less than negligible – indeed negative value – is what happens if you don’t vote. In Australia you get fined $55 if you don’t turn up at the polling booth. Interestingly this is regressive and likely to be a bigger consideration for people on lower incomes (who arguably are more likely to vote Labor).

Despite the social pressure and fines, in the 2007 election 453,000 Australians were fined (about 1 in 20 voters). So for some people a vote is worth not zero but -$55 dollars.

The informal votes (people turning up to the polling booth but incompletely numbering or leaving their voting paper blank) ran to 5.5% of voters in the 2010 election (of these informal votes about 1/3rd of ballot papers were totally blank).

A lot of irrational people around? Or is both the logic and the numbers telling us something that it would be irrational for us to ignore?

Is your non-vote worth more than a vote?

Even the most ardent supporters of compulsory voting would have difficulty arguing that refusing to vote can be a rational political act in some circumstances – for instance if you believe that the election result is fixed in a tinpot dictatorship and you boycott it.

Even the most ardent supporters of compulsory voting would have difficulty arguing that refusing to vote can be a rational political act in some circumstances – for instance if you believe that the election result is fixed in a tinpot dictatorship and you boycott it.

The boycott example helps us understand why people value not voting, as a number of informal and non-voters clearly do. Not voting is sometimes about the system – where you believe it’s the system not the politicians that’s the problem.

Anders Holmdahl, a non-voting South Australian, and a bunch of supporters are currently launching a Supreme Court challenge to compulsory voting, based on the distinction in the constitution that voting is a right versus the legislation arguing that it is a duty. It certainly hasn’t always been the case with compulsory voting enacted in South Australia in 1942 so there is a certain appropriateness to Mr Holmdahl’s choice to do this in South Australia which held out against compulsory voting longest of all the States.

Clearly Mr Holmdahl is also making a point about the system, whether or not you think his case has legs. As a barrister friend of mine says:

“the Supreme Court will listen politely for half an hour or so before dismissing the appeal. After that he can only appeal further with leave of the higher court. Typically he gets 20 minutes to persuade them to hear the case. He won’t. (Well I don’t think he will.)”

We should care about Mr Holmdahl and hope my barrister friend is wrong

In Australia one of the worst things about compulsory voting is that it masks political disengagement. Living in the UK in the aftermath of the UK 2001 election, which saw the lowest turnout in 100 years, a lot of questions were asked by media pundits, parties, and the public at large about what was wrong with the system.

In Australia in 2010 the informal vote was the highest since 1984 – but you’d have to delve into an AEC (Australian Electoral Commission) research report to find that out. Party membership of all stripes has collapsed by 80% over the last 50 years in Australia – what a great thing that we have compulsory voting otherwise we’d be asking some really searching questions.

Your vote is worth $2.31

There is another more subtle point about compulsory voting. It acts as a life-giving intravenous drip to sclerotic political parties due to the way the electoral commission funds parties based on vote share.

In the 2010 general election in Australia the parties got $2.31 per primary vote and by fining people for not showing up you are more likely to get a vote out of them.

Being generous and not choosing the US as a comparison does anyone seriously think Australia’s voting participation would be that different say from the UK’s 65% turnout without compulsory voting (for that matter do we think we get better quality governments than the UK does)?

The AEC payout was worth $10.8m dollars to the Labor Party or $8.7m dollars to the Liberal Party in 2010 somewhere between half and a third of their entire election budget, and if you’d been watching the press over the last few years you would have seen arguments that parties should be entirely publicly funded (because this would ‘prevent their being tainted by special interests’ – [cough] nothing to do with the fact that the major parties are slowly dying in their current form).

Interestingly, for new parties trying to establish themselves, they only receive this AEC shot in the arm once they get over 4% of the primary vote. So just at the time a new party might need it most it is only the incumbents who get the cash.

If Mr Holmdahl would be willing to lodge a complaint with the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, Australia’s competition regulator, about the cartel-like nature of Australia’s two biggest parties that would be great as well.

Non-voting is a valid choice and shouldn’t be criminalized

We’ve got to stop labeling the 9% of voters who don’t vote as non-community-minded, idiots, or just plain lazy.

Compulsory voting is a symptom of the underlying problem of political disengagement with our political system and not the solution. Just like in any tinpot dictatorship that boasts 90% turnout, 25% of our votes are bought and paid for (let’s not even go into the issue of donkey voters who number their cards from 1 to 10, or whether voters who are forced into the polling booth feel they are making an informed choice when they get there).

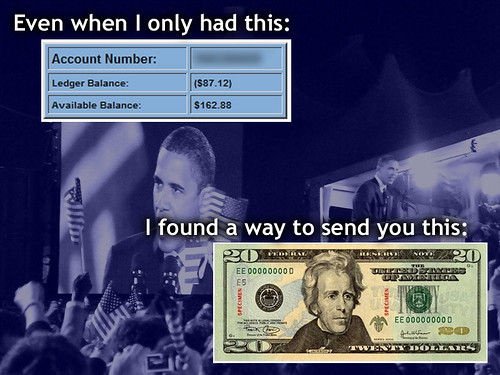

This is political theatre of the absurd. I didn’t vote in the 2010 election but not because I didn’t care about politics. I found none of the major parties compelling and happen to think that the way Victorian-era parties interact with the electorate inside and outside an election year is in need of root and branch reform.

But why should political parties change? They are going to get most people’s money and vote anyway.

Next election I’m planning to openly offer my (compulsory) vote to the highest bidder in an auction (in contravention of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 ) – the difference being that it will be public and not via the hidden AEC payment/fining mechanism.

What do you think? Is it the voters or the parties that really require compulsory voting?

This article filed under the following 'Interest' categories (click category for more) Hate pets, Unanswerable questions, Wait for release 2.0

Article posted by @Drivelry on April 15, 2012

Filed under topics (click for more articles on that topic): compulsory voting, election choice, party politics, political party funding

Agreed. And even with compulsory voting Australia’s turnouts are only 81% – lower than many countries where voting is compulsory including Sweden, Denmark, Iceland and Malta. And that 81% includes the huge number of donkey, informal votes and blind guesses. Compulsory voting causes political apathy by stealing our freedom when it matters most.